Lawler: Mortgage/Treasury Spreads, Part I

CR Note: In earlier posts, I used a quick and dirty historical comparison between the 10-year treasury yield and the 30-year fixed mortgage rate when discussing mortgage rates. For example, see How High will Mortgage Rates Rise? Of course, it is more complicated, as housing economist Tom Lawler explains.

From Tom Lawler:

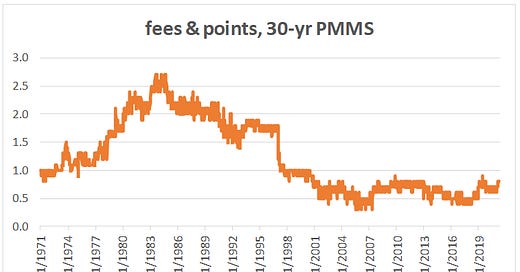

Many relatively unsophisticate…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to CalculatedRisk Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.